This article was originally published on the Journal of America’s Physician Groups on November 9, 2022 here.

Instead of forcing physicians to guess at correct code assignments, what if we allowed them to hand off the responsibility to expert risk-adjustment coders?

The U.S. is in the midst of a public health crisis. Simply put, healthcare demand has risen beyond our current capacity to meet it.

Today, 80% of rural Americans 1 live in medically underserved areas, known as healthcare deserts, and the problem is worsening each year. Healthcare deserts also exist in urban environments, especially those populated by historically marginalized groups. Physicians and other types of healthcare providers are in short supply in many areas of the country. Compounding this issue, the number of Medicare enrollees is expected to grow by 26% 2 over the next few years, and the population of people living with multiple chronic conditions 3 is rapidly increasing as well.

Meanwhile, many physicians are suffering from burnout, a form of exhaustion caused by constantly feeling swamped. Adding even more patients on top of a system that is already overtaxed will only worsen the strains.

To address these issues, we must think about how we can extend the capabilities of providers and relieve them of nonclinical tasks to increase their capacity to care for patients — without adding to their already full plates. One of the first steps provider organizations can take to address provider burnout is to implement and operationalize Hierarchical Condition Coding (HCC) programs.

Providers’ Administrative Burden: A Growing Problem

For many years, providers have been performing more than the lion’s share of administrative work. According to a 2016 study in the Annals of Internal Medicine, 4 for every hour physicians spend seeing patients, they spend nearly two additional hours on paperwork. A more recent study 5 found that physicians spend an average of just over 16 minutes on electronic health records (EHRs) for each visit — a length of time that frequently exceeds the actual visit with the patient.

Considering that most primary care providers (PCPs) see approximately 20 patients a day, 6 the paperwork quickly adds up. In addition, providers who report six or more hours of after-hours charting per week are 50% more likely 7 to report burnout—a leading cause of physician turnover. The need to reduce administrative workloads is clear.

COVID-19 has provided a startling glimpse into the future of healthcare if we do not address these systemic issues—and highlighted the need to reduce administrative workloads and optimize coding processes. The pandemic has also emphasized what healthcare workers have long known: the value of having accurate data to make real-time decisions, all of which are driven by medical coding.

While future pandemics or healthcare crises can’t be prevented, it is possible to increase the supply of providers who are ready and able to serve patients—and not bogged down in administrative work. Appropriate coding is part of the solution.

Delegating Coding to the Experts

Medical coding translates diagnoses, procedures, medical services, and equipment into universal medical alphanumeric codes, typically for the purpose of payment. A shift is underway across U.S. healthcare from the use of so-called Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) coding, which captures medical, surgical, and diagnostic procedures and services, to Hierarchical Condition Coding, which captures multiple conditions and drivers of a patient’s health status and prognosis over a long period of time. HCC, which links in turn to the International Classification of Diseases 10 th Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis coding system, was adopted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in 2004 as a risk-adjustment tool, and is now central to the operation of Medicare Advantage and other value-based care programs. HCC is used to assign patients a so-called risk adjustment factor (RAF) score, which is used in turn to predict the costs of providing healthcare to them over time.

With CPT coding, providers choose from a subset of approximately 10,000 codes for their specialty and practice capabilities. These codes have been created by the medical specialists who perform the procedures (the American Medical Association). In contrast, HCC coding includes more than 72,000 ICD-10-CM codes for providers to choose from. Diabetes alone has 300 codes.

This increased specificity is intended to provide more detailed information for measuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of care. However, the ability to transcribe clinical documentation into the complex ICD-10 classification system requires skills that are often outside of and counterintuitive to clinical expertise — making it harder for providers to find the codes they need for reimbursement.

Another problem with having providers undertake coding is that if mistakes are made, they often are not caught. Coding errors are primarily identified through retrospective reviews. While these reviews are necessary as part of quality assurance and compliance programs, value-based care is focused on preventing and managing disease. Retrospective reviews often occur long after the opportunity to benefit the patient or identify and address emerging population health trends in a timely manner.

Instead of forcing physicians to guess at correct code assignments from lists on electronic health records, what if they handed off the responsibility to expert risk-adjustment coders? As of 2015, only 18% of practices had full-time medical coders on staff. If more provider organizations delegated coding to experts, the industry could effectively address the root cause of process issues that lead to administrative burden.

Prospective or Concurrent Coding?

HCC can take place in three ways: prospectively, as in before a patient visit to help physicians identify suspected conditions; concurrently, which occurs after a visit but before the medical record is submitted for evaluation and payment; and retrospectively, which can occur a year or more after an encounter. Prospective coding (also known as pre-chart prep) and concurrent coding provide the advantage of offering an immediate opportunity to use coding data to improve clinical practice, whereas retrospective coding offers no opportunity for immediate clinical impact.

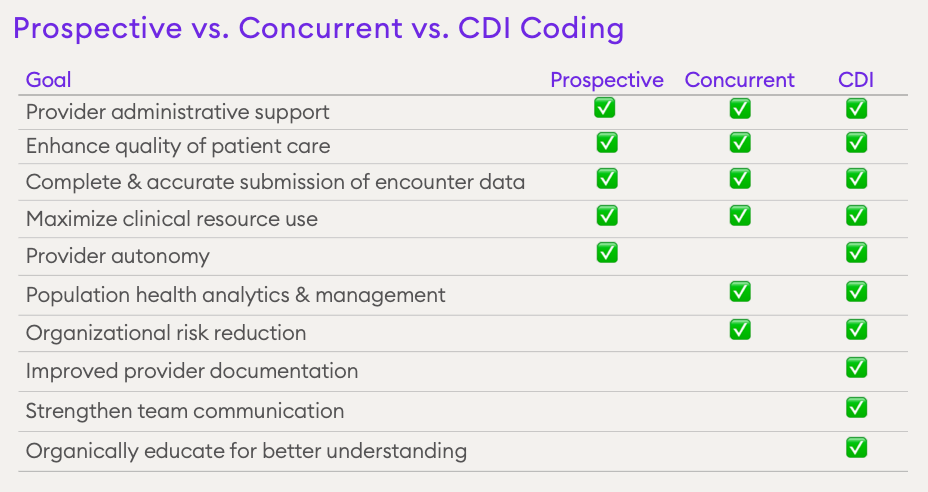

Although prospective and concurrent coding have slightly different goals (see Figure 1), they both aim to support complete and accurate documentation of encounter data and maximize the use of clinical resources. They are frequently accompanied by another process, clinical documentation improvement (CDI), which is the process of reviewing medical record documentation for completeness and accuracy.

Benefits for Patients and Providers

With these considerations in mind, having expert coders undertake HCC, rather than providers themselves, can produce important benefits, as follows:

1. Supporting complete medical record data. When providers focus on documenting correctly in the medical record, while coders focus on coding, better and more complete medical records result. With better data come better treatment and outcomes — and reduced costs of care.

2. Reducing clinician malpractice risk. Diagnostic-related issues are the biggest root cause of malpractice claims. Removing the responsibility of coding from providers, who may code a condition inaccurately, may mean less risk of diagnostic failures.

3. Supporting compliant risk-adjustment practices. Provider organizations that use expert coders will capture a more complete picture of a patient’s health, which can help ensure adequate funding for care in risk-adjustment payment models.

HCC Coding and the Future of Care

While healthcare organizations may have lofty goals for patient outcomes and financial performance, these goals cannot be accomplished without excellent clinical care.

Provider organizations that seize the opportunity to change their infrastructure and administrative processes today will be better poised to navigate the future of healthcare — not just for tomorrow but for years to come.

References

1 Health care deserts: nearly 80 percent of rural U.S. designated as ‘medically underserved.’ KHN Morning Briefing, Kaiser Health News. Sept. 30, 2019. https://khn.org/morning-breakout/health-care-deserts-nearly-80-percent-ofrural-u-s-designated-as-medically-underserved/.

2 Medicare beneficiary demographics. MedPac. July 2021 Data Book, Section 2: page 22. https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/ July2021_MedPAC_DataBook_Sec2_SEC.pdf.

3 Chronic conditions: making the case for ongoing care. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. February 2010. https://smhs.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/ ChronicCareChartbook.pdf.

4 Sinsky C, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Dec 6;165(11):753-760. doi: 10.7326/M16-0961.

5 Overhage MJ, et al. Physician time spent using the electronic health record during outpatient encounters. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Feb 4;172(3):169-174. doi: 10.7326/M18-3684.

6 Weber DO. How many patients can a primary care physician treat? American Association for Physician Leadership. February 11, 2019. https://www.physicianleaders.org/news/how-many-patients-canprimary-care-physician-treat.

7 Eschenroeder HC Jr. Associations of physician burnout with organizational electronic health record support and after-hours charting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021 Apr 23;28(5):960-966. doi: 10.1093/ jamia/ocab053.

8 Terry K. Many Physicians Still Unprepared for ICD-10. Medscape. June 22, 2015. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/846790.